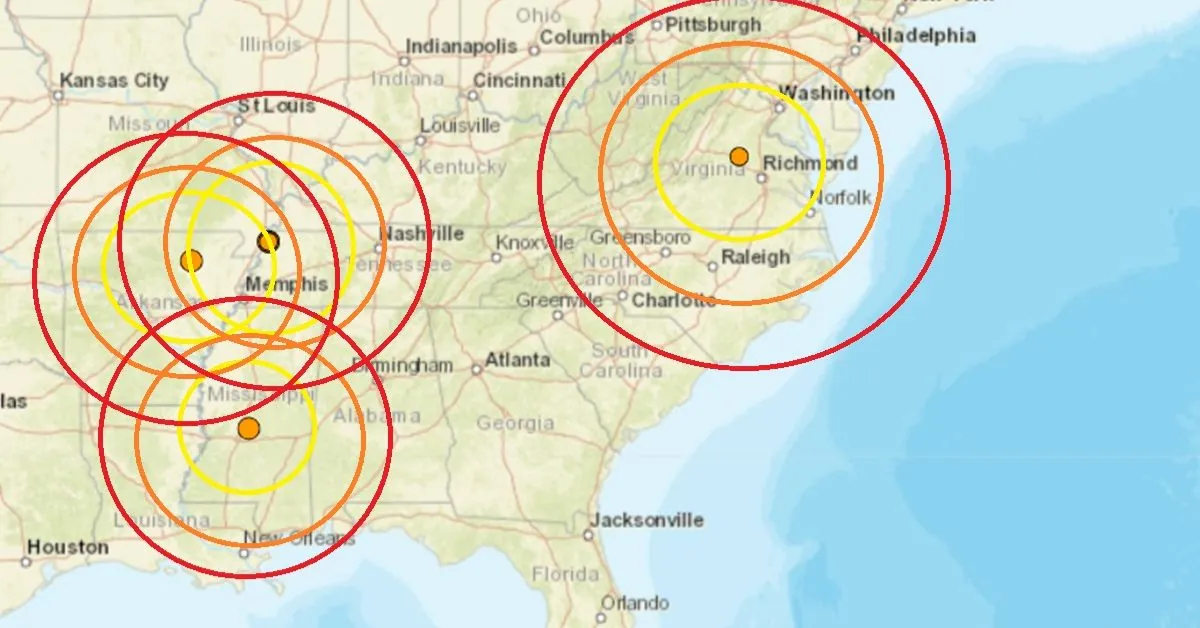

The USGS has reported earthquakes in Virginia, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas on Thanksgiving Day. The strongest of the group struck Mississippi, with a magnitude 2.5 earthquake. The others ranged from magnitude 1.8 and above; while some felt shaking or heard a boom, none caused any damage or injuries.

Last night, shortly before midnight, the first strike hit central Virginia. At 11:39 p.m., a magnitude 1.8 earthquake struck near Louisa, Virginia, north and west of Richmond, from a depth of 0.3 kilometers.

At 1:48 a.m., the second earthquake struck Mississippi from a depth of 5 kilometers, near Canton, which is located north and east of Jackson.

The following three earthquakes occurred in western Tennessee, beginning at 4:23 a.m., followed by 4:39 a.m. and 4:59 a.m. At 5:08 a.m., a fourth earthquake struck the same approximate location. The depth of these earthquakes varied from 5.9 km to 6.1 km, and they struck near Ridgely in the New Madrid Seismic Zone.

At 4:24 a.m., another earthquake rocked Strawberry, Arkansas. The magnitude 2.1 event occurred at a depth of 8 kilometers and is believed to be part of the New Madrid Seismic Zone.

While the earthquakes last night were relatively minor, with no damage reports, authorities are concerned that people are not adequately prepared in case a major earthquake strikes this region. The likelihood of a larger catastrophic earthquake here is more “when” than “if.” In particular, these earthquakes in Tennessee occurred within the New Madrid Seismic Zone, also known as the NMSZ. Although they and the other two quakes were minor, they occurred in a region where a major earthquake is likely to occur again in the future.

Experts predict a repeat of the NMSZ’s violent past, but no one knows when.

Scientists predict a replay of the devastating period in the region’s seismological history, which began with the first of three large quakes that struck the United States during the winter of 1811-1812, on December 16.

Many people are unaware that one of the country’s largest quakes occurred near the Mississippi River, despite the US West Coast’s well-known seismic faults and powerful quakes. On December 16, 1811, at around 2:15 a.m., a massive 8.1 quake shook northeast Arkansas, forming the New Madrid Seismic Zone of today. The earthquake shook people awake in New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, South Carolina. In regions badly struck by the earthquake, such as Nashville, Tennessee, and Louisville, Kentucky, the ground shook for an unbelievable 1–3 minutes. Near the epicenter, the ground motions were such that they caused liquefaction, hurling tens of feet of mud and water into the air. President James Madison and his wife, Dolly, felt the earthquake in the White House while church bells sounded in Boston as a result of the shaking.

However, the earthquakes did not finish there. Between December 16, 1811, and March 3, 1812, the middle Midwest registered over 2,000 earthquakes, with Missouri’s “Bootheel,” home to the New Madrid Seismic Zone, experiencing 6,000-10,000 earthquakes.

The second major shock, a magnitude 7.8, struck Missouri on January 23, 1812, while the third, a magnitude 8.8, impacted Missouri and Tennessee along the Reelfoot fault on February 7, 1812.

The primary earthquakes and the severe aftershocks caused enormous damage and some deaths, but the absence of scientific equipment and news gathering at the time prevented them from capturing the entire scope of what had occurred. In addition to shaking, the earthquakes caused uncommon natural phenomena in the area, such as earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake haze.

Residents of the Mississippi Valley reported seeing lights flashing from the ground. Scientists surmise that this phenomenon, known as “seismoluminescence,” stems from the compression of quartz crystals in the earth. The “earthquake lights” went off during the major quakes and powerful aftershocks.

The Mississippi River and the ground both threw extremely warm water into the air. Scientists assume that extreme shaking and friction caused the water to heat, similar to how a microwave oven causes molecules to shake and generate heat. Other experts believe that the compression of the quartz crystals produced light that assisted in warming the water.

During the violent quakes, the skies became so dark that people reported lighted lamps did not assist in brightening the region; they also claimed the air smelled awful and was difficult to breathe. Scientists believe dust particles rising from the surface, combined with the ejection of heated water molecules into the frigid winter air, generated this “earthquake smog”. As a result, a steamy, dusty haze engulfed the areas affected by the earthquake.

The February earthquake was enough that boats on the Mississippi River reported that the flow of water reversed for several hours.

The area is still seismically active, and scientists anticipate another large quake will hit the region in the future. Unfortunately, the science isn’t advanced enough to predict whether that threat will strike next week or in 50 years. In any case, with the population of the New Madrid Seismic Zone much larger than the sparsely populated area of the early 1800s, and tens of millions more people living in an area that would experience significant ground shaking, there could be a significant loss of life and property if another major earthquake strikes here again in the future.

Leave a Reply