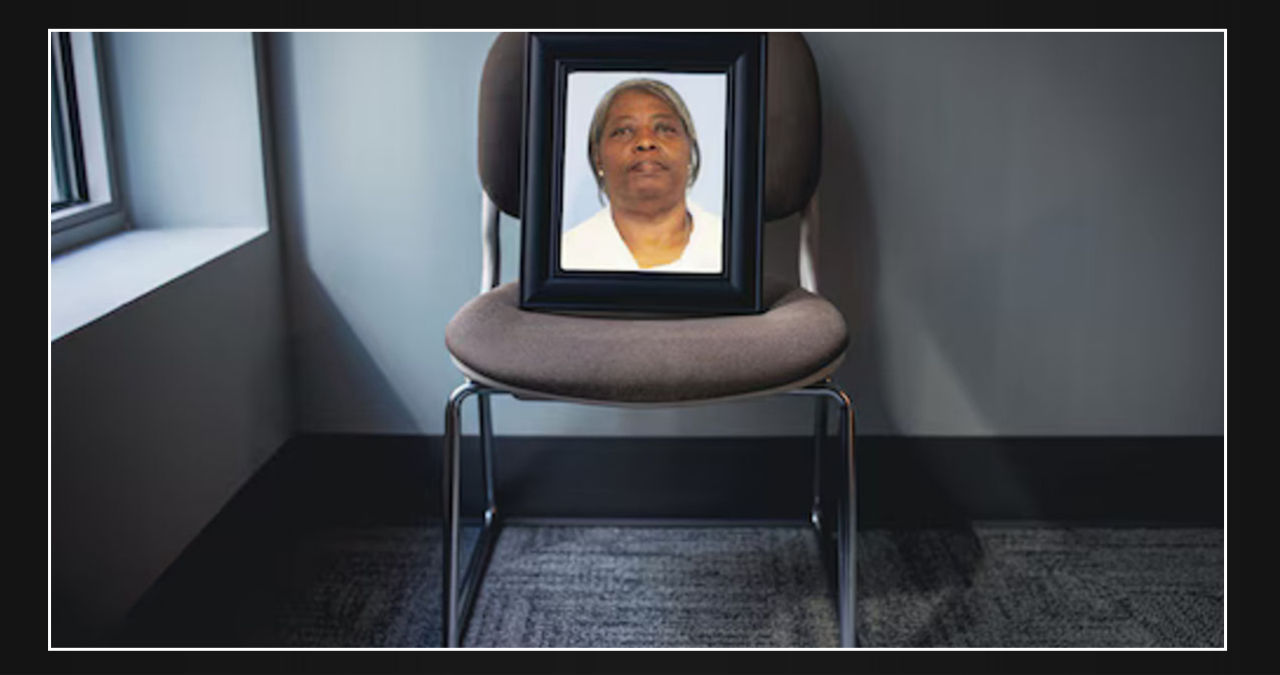

Leola Harris spends her days in a wheelchair, sitting through three days of dialysis and recovering from the other treatments.

“Your decision today should be an easy one,” her attorney, Ashleigh Woodham, told the Alabama parole board.

In 2023, this board had already denied Harris parole. However, Harris was so unwell that the prison system chose to bypass the parole board and send her home on a rare medical vacation earlier this year.

That did not, however, guarantee her immediate release.

However, as her attorney noted this week, her release should have been a simple decision. Woodham stated that her client undergoes renal dialysis three days a week, “pretty much locked into a machine.”

“(The prison system) got it right when it granted furlough,” she told me.

The shooting death of 45-year-old Lennell Norris has led to Harris’s imprisonment. Harris welcomed the man inside her home in the little hamlet of Shorter, Macon County, early one morning in May 2000. She claimed she discovered him dead in her kitchen later that morning. She initially reported to authorities that Norris shot himself while she was sleeping in her bedroom. Court filings contain the autopsy report, which states that Norris’ cause of death was unknown and there were differing perspectives on whether he could have fired the trigger.

In 2003, a Macon County jury heard the case and found her guilty of murder. Harris claimed that she fell ill shortly after her incarceration.

Prior to her furlough release this summer, she had lived in the Julia Tutwiler prison infirmary for the previous five years.

While Harris is already physically released from prison, she must adhere to rigorous conditions while on furlough and cannot travel more than a specific number of miles from her Shorter residence. Obtaining parole would allow her to travel the state and seek medical care at Birmingham-area hospitals if necessary.

Woodham, who works for the organization Redemption Earned, told the board that “Leola will only get older and sicker from here.”

Not everyone was convinced, however.

Darryl Littleton was the only parole board member who questioned the attorney, inquiring about Harris’s time on furlough and her current circumstances.

Leigh Gwathney, chairperson of the Parole Board, and board member Gabrelle Simmons asked no questions of either side.

Representatives from the NGO Victims of Crimes and Leniency and the Alabama Attorney General’s Office spoke briefly, urging the board to refuse Harris parole. The vocal representative used the same language at all three parole hearings on the schedule that morning: the victim “will no longer be able to build relationships” with their loved ones.

The attorney general’s office official stated that the case involved “horrendous facts” but did not go into depth regarding the crime. Neither of the board members inquired about it.

Harris must wear a GPS ankle monitor as part of her parole conditions.

In the end, the board divided 2-1 and awarded Harris parole. Even though the prison system had already released her, Gwathney voted to deny Harris parole and requested that she not return for another hearing for two years.

Parole rates have risen in 2024. Last year, Alabama’s parole rate was barely 8%. The board’s own standards suggest that approximately 80% of inmates should have received parole. However, as attention from the media, the public, and lawmakers increased, the board began to split votes. Some months, the board releases three times as many people.

According to bureau data, the board granted 21% of all paroles in July. This year, the monthly grant rates have fluctuated between 17% and 24%.

Harris was the lucky one on Tuesday morning at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles’ downtown Montgomery location.

The other two individuals up for parole in Harris’ case were both convicted of murder, one serving a life sentence and the other a 25-year sentence.

In one of those cases, the inmate’s son stood up, a teen wearing a shirt with the ‘Peanuts’ characters Snoopy and Woodstock on the back, and the words “it’s good to have a friend.” He could not finish his prepared address to the board without crying.

In this case, the victim’s family had the same reaction, with his mother sobbing and his sister speaking so quietly that the microphone could hardly pick up her words.

Both men were denied; one will have another hearing in four years and the other in five.

Leave a Reply