On March 23, 1945, four white police officers entered Hattie DeBardelaben’s property in Alabama. They accused her of manufacturing and selling untaxed whiskey.

Denying the allegation, the 46-year-old Black mother of seven children welcomed the police to search her property.

However, the cops killed her by repeatedly hitting her and breaking her neck in front of her 15-year-old son, who was jailed for attempting to defend his mother.

An FBI investigation, initiated at the request of the NAACP, concluded that she had passed away due to a heart attack. Consequently, the case was closed a few months later. It is noteworthy that Clyde Smith, one of the police officers involved in her unfortunate demise, went on to become the sheriff of Autauga County.

Last month, after decades of being kept secret, the case was finally brought to light. The National Archives and Records Administration released 69 pages of documents from the investigation under the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act. This act was signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2019.

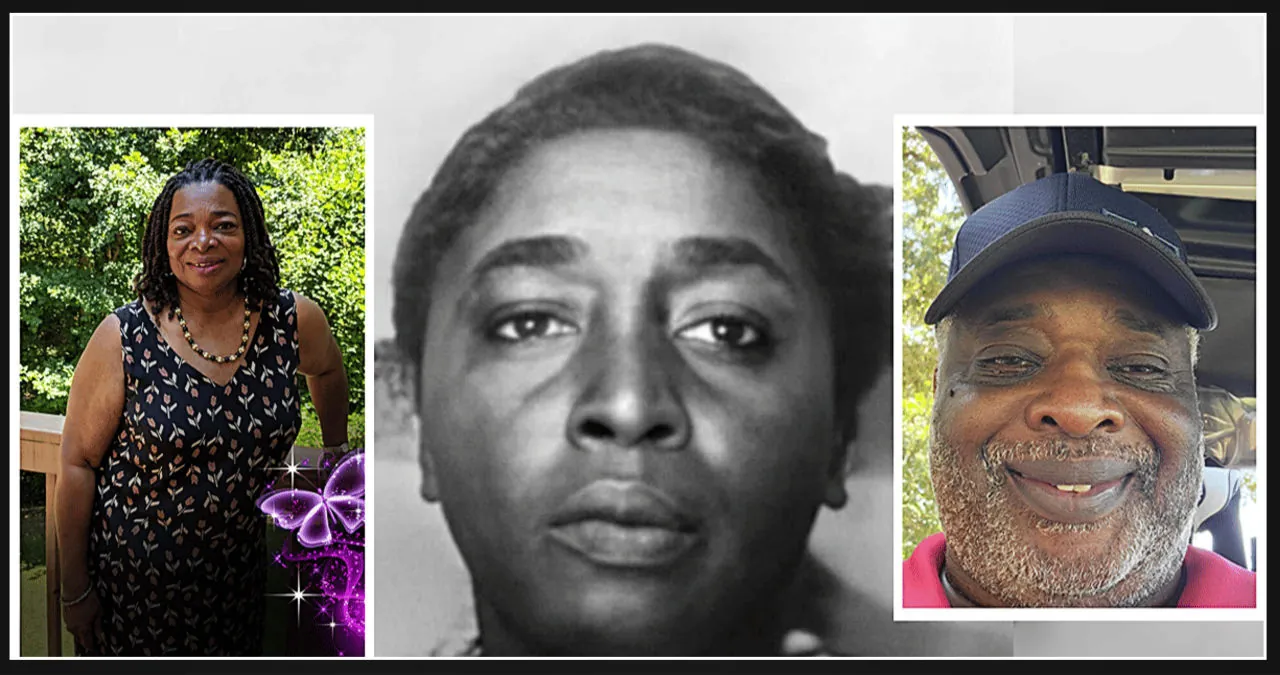

The first set of records released under the act focused on the cold case of Hattie DeBardelaben, bringing a sense of closure to her grandchildren. Their parents had never disclosed the details of their grandmother’s death to them before.

“I cried for a couple of days, because I couldn’t believe what had happened to my grandmother,” Mary DeBardelaben, 74, told AL.com .

“It was a cover-up,” her brother, Dan DeBardelaben, told CNN . “That’s what happened — these documents make it clear.”

The documents, available for reading here, here, and here, illuminate a horrific murder case involving law enforcement officials and the tragically ongoing government cover-up.

“The name Hattie DeBardelaben may be unfamiliar to most people, but her death at the hands of law enforcement officers in 1945 was sadly typical of the violence – and even lethality – that many Black Americans suffered in the Jim Crow South,” Margaret Burnham, co-chair of the Civil Rights Cold Case Review Board, said in a statement.

“Although her death was investigated by federal agents at the time, the perpetrators were never held accountable. However, we hope that the release of these records after all these years provides some answers to her descendants while also illuminating a dark chapter in our nation’s history.”

The Murder

This Article Includes [hide]

Clyde White, a former Autauga County sheriff’s deputy, reported to the FBI that he had been receiving complaints about DeBardelaben’s involvement in the illegal sale of whiskey. In response, he reached out to agents from the federal Alcohol Tax Unit, the predecessor of the current Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives agency.

White arrived at DeBardelaben’s farm accompanied by three ATU agents named John H. Barrenbrugge, J.C. Moseley, and L.O. Smith.

According to White, they discovered a quart of whiskey and some empty jugs with a whiskey scent. Based on this, they made the decision to arrest her for the possession of whiskey. Additionally, Edward was arrested for allegedly interfering with the arrest. However, White did not provide specific details on how Edward interfered, only stating that he made a comment about the officers’ ability to search the house.

According to his account, DeBardelaben passed away unexpectedly in the rear seat of the vehicle while they were en route to the county jail in Platville.

DeBardelaben’s 15-year-old son, Edward Lewis Underwood, gave the FBI a contrasting account of the events. According to him, upon returning home from school, law enforcement officers arrived at their family farm in a rural area outside Selma. They approached his mother and inquired about the possibility of purchasing whiskey.

According to him, his mother informed the officers that she did not have any whiskey and willingly allowed them to search the house, despite the absence of a warrant.

Her 16-year-old nephew, James Callier, arrived home from school and was confronted by the officers. They instructed him to sit on the ground, but it seemed like he didn’t hear them. In response, one of the officers approached him and unexpectedly punched him. This caused Callier to quickly join his aunt, Underwood, on the ground.

Edward recounted a horrifying incident in which the police officer, who had previously assaulted his cousin, approached his mother and delivered a forceful blow, causing her to stumble and accidentally land on a pot of boiling water she had been using for laundry.

As she attempted to rise, two ATU agents delivered another blow, causing her to stumble and collide with the pot of boiling water.

She rose to her feet once more, only to be struck down again by both of them. As a result, she dropped to her knees, her palms planted firmly on the ground.

After experiencing nausea, they decided to pull over so she could safely vomit on the side of the road. Once she had finished, Edward carefully helped her back into the car and they resumed their journey. However, shortly after, she suddenly lost consciousness.

The Cover-up

Dan Albright, a Black undertaker from a local funeral home in Platville, told the FBI that the sheriff had contacted him to pick up the body from the jail at 6:30 p.m. that day. Albright stated that her body was still in the back seat of the police car, and she was “foaming at the mouth and nose just like a boar hog foams.”

He also stated that the sheriff phoned Dr. James Tankersley, who examined her body while it was still in the police car and declared she died of a heart attack, despite indicators that she had fractured her neck.

“The only thing I noticed that was different from other bodies was that whenever we picked up the body, the head would fall back,” Albright told investigators. “I said nothing to the doctor about the neck. After his examination, the doctor said she died from heart trouble.”

That evening, at Edward’s request, another Black undertaker named Fred Williams picked up the body from the initial funeral home in Plattville and transported it to his funeral home in Selma, where he examined it the next morning and determined she did not die from a broken neck, but without dissecting it.

He also mentioned that rigor mortis had set in more than 12 hours after her death, making a full determination impossible.

According to a 2016 medical study, it is difficult to make a complete diagnosis about a fractured neck without dissecting it:

First, it is essential to dissect the neck properly at postmortem examination. This entails the layer by layer dissection of the anterior neck following vascular decompression of the neck by removal of the brain and the viscera (2). The dissection of the neck is best achieved by a series of incisions that provide for maximal exposure of the ventral, lateral and submental portions of the neck. This dissection can often be extended to involve the face. Second, it is vitally important to proactively recognize the pitfalls and artifacts that may be apparent based upon the history, scene and circumstances surrounding the case. The prepared mind will be unlikely to fall into diagnostic traps related to misinterpretation of observations of no significance.

Rigor mortis, or muscle stiffening after death, affects the neck within hours, peaking at 12 hours, according to a 2023 medical study.

The FBI also conducted an interrogation with DeBardelaben’s ten-year doctor, a white man named J.S. Chisholm. He told agents that her health had always been perfect until about a month ago, when she complained of shortness of breath and swelling in her feet.

He diagnosed her with a heart murmur and informed her she might probably live a normal life, “but it was not at all unusual to have a person in her condition drop dead very suddenly, particularly if they had been subjected to any unusual strain or excitement.”

That was all investigators needed to close the case on June 30, 1945, concluding that the cops had done nothing wrong and stating the following in their report.

Our investigation reflected that she had recently had a heart attack and had been under treatment by a local Doctor Who stated that her condition was such that any unusual excitement might cause her death. The Doctor Who examined her subsequent to her death discovered no evidence that DeBardelaben had been beaten or otherwise mistreated prior to her death and stated that her death was caused by a heart attack. The arresting officers denied having beaten the victim.

Dan and Mary DeBardelaban, whose father was Bennie DeBardelaban, one of the young men working in the fields when their mother was slain, now realized why their family never told them about their grandmother’s death, even when they visited her grave as children. All seven of her children have passed away.

“My dad and his brothers and cousins, you know, got to witness what actually happened,” Dan told AL.com.

“Seeing that, I’m sure, was so traumatic for my father and was one of the reasons that he never said a single word, nor did he or his other six sisters and brothers ever have a conversation with us about what took place.”

Leave a Reply